Gall wasps parasitize plants by laying their eggs in them. They lay eggs in stems, leaves, flowers, buds, seeds – you name it, they lay it. And as that egg grows into a larvae, the plant grows around the egg forming abnormal structures or galls. Typically these galls are bulbous, but sometimes they’re subtle and you wouldn’t notice their presence at all. A few scientists have though.

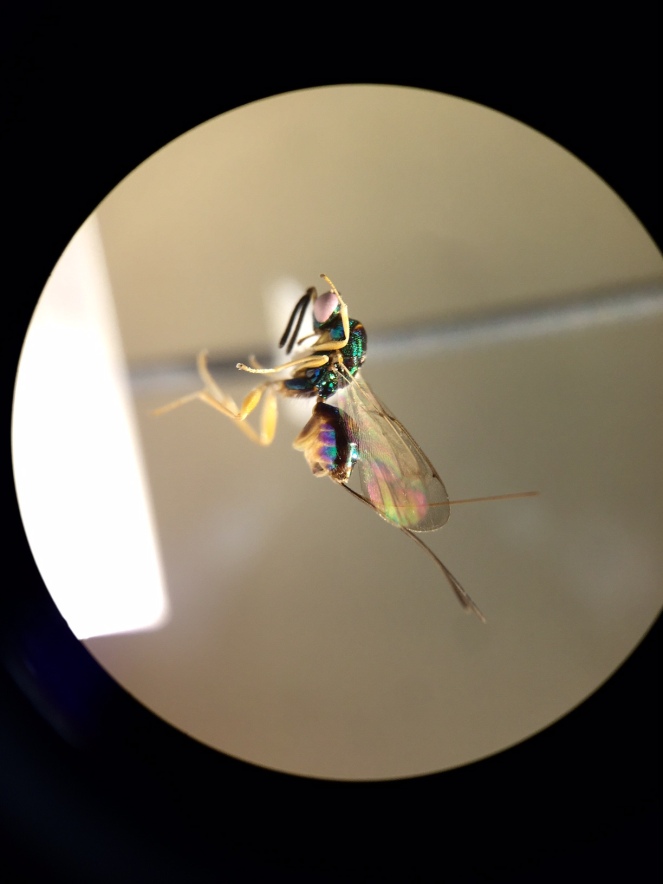

Mike Gates, Kenji Nishida, and Paul Hanson have collected several galls over the past few years in Costa Rica. With patience, they collected and raised these galls to discover what was growing inside. The wasps that emerged sometimes still had parts of their pupal sheath on, not yet fully relieved of their childhood skin, before they were caught and preserved. Those wasps now rest on cardstock, point mounted in nice neat rows awaiting identification in the back offices of the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History.

Those same offices were where I started testing my love for insects two years ago. Over the summer of 2014, I spent over 380 hours identifying wasps under the guidance of Dr. Gates. Alone, I traveled to D.C., knowing no one and scraping together a living situation from Craigslist. It was scary, but I didn’t think twice about doing it. I wanted to intern at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History. I wanted to learn more about entomology and if my decision to switch my major from English to biology really was a good idea. And it was a good idea! I realized how much I love entomology and how I strangely enjoy the tedious work of taxonomy.

Taxonomy is man’s attempt to assign order to the chaos of evolution. That attempt is hard work, piled into volumes of scientific publications that fill Dr. Gates office at the museum. As an intern, I couldn’t begin to explore those papers. I was still stuck in the dichotomous keys identifying only as far to genus. If I wanted to name a species, I was going to have to earn it.

Last summer I designed and found funding for my own trip to Costa Rica where I met Paul Hanson and Kenji Nishida. Names were given meaning as I met the people who had discovered much of the wasp biology that I knew, and as I finally saw the biological diversity that I had studied in college. I collected my own wasps, raised some galls, and preserved them so my wasps could be added to the collection. (You can read more on that whole trip here).

Now I’m back at the museum, not as an intern, but rather a research collaborator. I feel like I graduated into a new apprenticeship as I work in Mike Gates’ office. Having visited their habitats, I’m thrilled to identify these gall wasps to species now. The journey will require a lot of patience, and although I only have two weeks, I think I can make it. Two days in, and Gates and I have ID’d most of the wasps to genus. Today I spent nine hours swimming through online databases and descriptions of species from genus Galeopsomyia. After becoming quite leery of descriptions of new species based on single characteristics and specimens, I finished the day off by exploring the cabinets of Gates’ office. In there I found documents from as far back as 1843. Most were typed, but some remained of handwritten descriptions in Latin. Journal entries like secret diaries of the wasps they found in the underbrush on their trips. Walker, Ashmead, and Howard are all men who have long since passed on. But their notes and contributions to science remain. They’re the foundation of my research and I’m mesmerized to feel this connection across time of a love for insects.